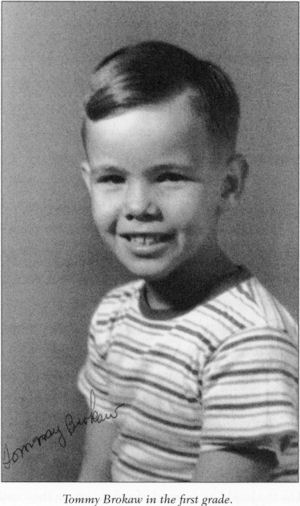

The above photo is on page XVI of the following book by Tom Brokaw.

A Long Way From Home

Growing Up in the American Heartland

By Tom Brokaw

Random House, 2002

pgs. 62 to 66

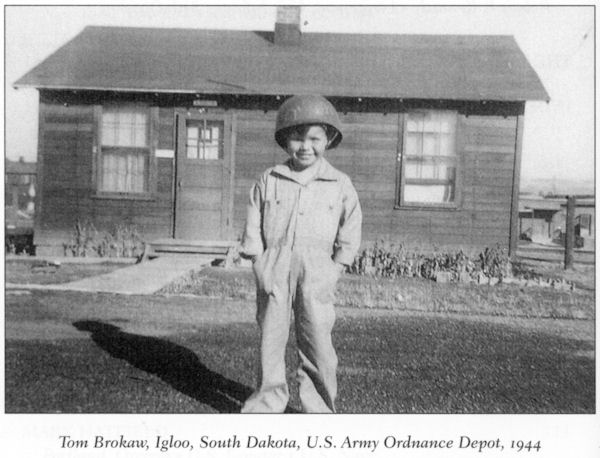

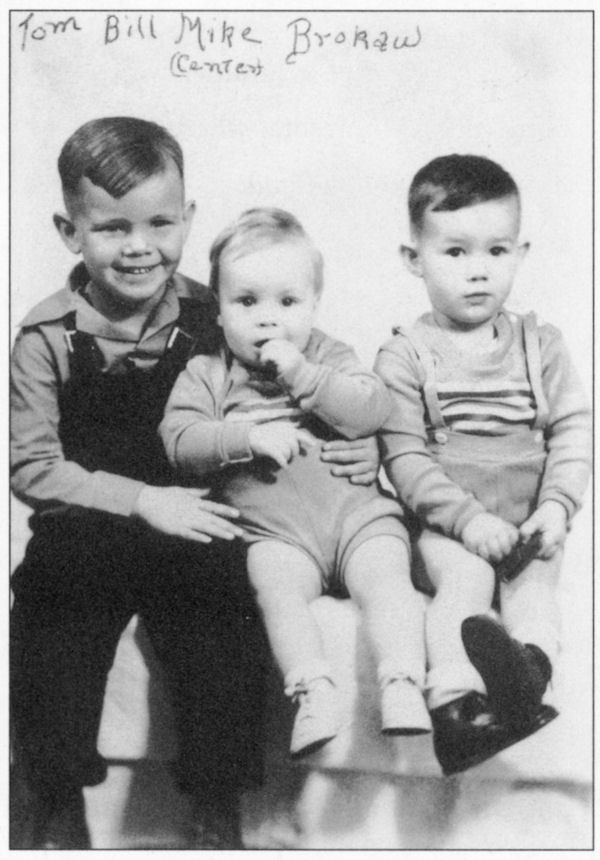

The Brokaw brothers at the Army Ordnance Depot in Igloo, South Dakota, 1944.

By then I had a baby brother, Bill, ten months old, and Mother was expecting a third child in a few months. Dad heard about a job at a new Army ordnance depot - a storage facility for bombs and artillery shells - scraped out of the sagebrush hills of southwestern South Dakota. The base was called Igloo, after the ordnance storehouses on the arid landscape that were shaped like Eskimo igloos. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was responsible for making sure the base functioned smoothly, and Dad was hired at $6.88 a day.

As he awaited his call to service, Red worked at keeping the new base operation, plowing snow, building roads to the storage bunkers, repairing the fleet of cars and trucks, all painted U.S. Army olive green. When his draft notice arrived, he passed his physical and planned to enlist in the Navy. He thought his skills would be best used in the Navy's construction branch, the Seabees. But the colonel running the ordnance depot called Red back, saying he was more important to that facility than he would be in the Navy. So I had a stay-at-home dad for the remainder of the war, one who was making his contribution in civilian clothing rather than a military uniform. He was thirty-two at the time. As for me, I had never known any time when the country was not at war and I suppose I thought it would go on forever. At ages three, four, and five I was shooting imaginary Japanese and German soldiers from the cover of a shallow ditch in front of our small government house on the base. My "weapon" was a wooden gun my father had carved out a piece of scrap lumber. Most of our toys were handmade, as toy production was put on hold for the war effort. One Christmas, almost every present for the Brokaw boys had been handcrafted by our father or one of his fellow workers at the shop, as they called the large garage where they reported to work daily. We got a wooden wagon, carved wooden cars, and a toy pistol turned out in the metalworking shop. Forty years later I returned to what remained of Igloo with my parents and my own daughters. We found the foundation of our old house, which had a coal stove in the living room for heat and an old-fashioned wood-burning cookstove on which Mother prepared meals and heated water for baby brother Mike's baths in a washtub. Dad and his granddaughter Sarah, our youngest child, walked off the foundation and estimated that the entire house was twenty feet by twenty feet, about the size of her bedroom in our New York apartment.

While Dad was at work in Igloo, Mother was at home with three boys under the age of four. My youngest brother, Mike, had been born at the base, just fifteen months after Bill. We were confined to that small space during the harsh winter months, and yet I cannot recall any sense of hardship or any bickering between my parents. As my mother likes to remind me, "Everyone was in the same boat."

My entire world, from the surrounding arid hills to the uniforms and vehicles, was khaki brown or olive green - except for some strangers confined to a stockade on the edge of Igloo, who wore bright orange uniforms and spoke a strange language in rapid fire fashion. They were Italian prisoners who had been shipped a long way from the front lines of southern Europe to sit out the war in South Dakota.

Security was not exactly airtight; the POW's were allowed to wander through town on their low-grade job assignments, mowing lawns, picking up litter, and working as orderlies in the hospital. Many years later, Mother confided to me that a few of them struck up romantic liaisons with war widows. Curiously, although I recall so much of a child's life from that time - sledding in winter, fishing trips, the movie Song of the South, the names of playmates and my kindergarten teacher, even the whipped cream the police chief's wife, a nurse, served on their Jell-O desserts - I have no specific memory of the death of Franklin Roosevelt. FDR was a demigod to my parents and grandparents, so it must have been a terrible blow when he died in 1945. But, perhaps because the news came by radio - so it was not visual - it failed to register on my five-year-old consciousness. I do remember, though only vaguely, the celebrations when the war was over. Edgemont, a tough little ranching town next to the ordnance base, was where the young soldiers went to drink and gamble and it was there they spilled out onto Main Street to raucously toast the victories.

pgs. 94 & 95

"In my mind's eye, I can still see my first public performance. It was in a large hall crowded with men in uniform and the civilians who performed the nonmilitary tasks at Igloo. It was Christmas, 1944; I was just four years old, and I had been chosen to open the holiday pageant. Although the scene remains quite vivid in my memory - the smoke from hundreds of lit cigarettes forming a blue haze over the proceedings, the wooden folding chairs, and the ropes of tinsel looping along the walls - alas, I can remember only the opening line of my welcome to the crowd. It began, "They said I was too young to speak a piece tonight . . . ," but the rest is lost in the black hole of more than half a century of other impressions crowded onto the recollection cells. What I do remember is that I was paid for my performance. My father stood at the back of the hall and held up a silver dollar. If he could hear my every word, he said, I would get that silver dollar. It was an enormous sum for a four-year-old at a time when a nickel would buy a huge ice cream cone. I just loved to talk and I soon had an opinion on just about everything. Fortunately, my parents and my teachers indulged me. I was quick to raise a hand in class and, unlike most of my classmates, I wanted to be chosen to read aloud. By the time I reached second grade, my motor mouth was fully engaged."

(The Brokaw's came to BHOD from a construction job near Alexandria, MN and when the war ended moved on to the Fort Randall Dam project at Pickstown, SD)

(As a reference to the dates; Red Brokaw was born Oct. 17, 1912 and Tom Brokaw was born Feb. 6, 1940.)

(Tim Russert interview)

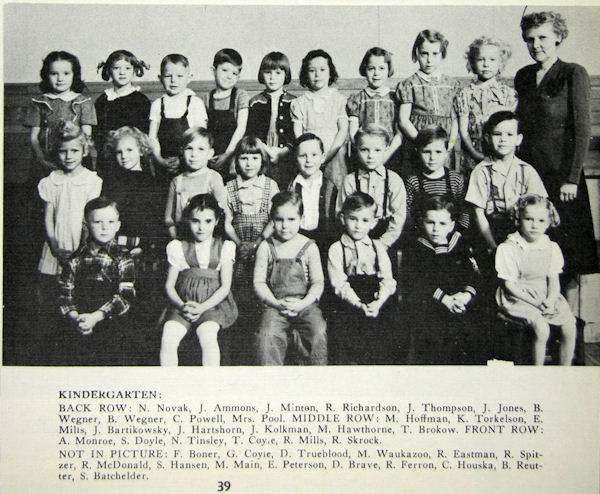

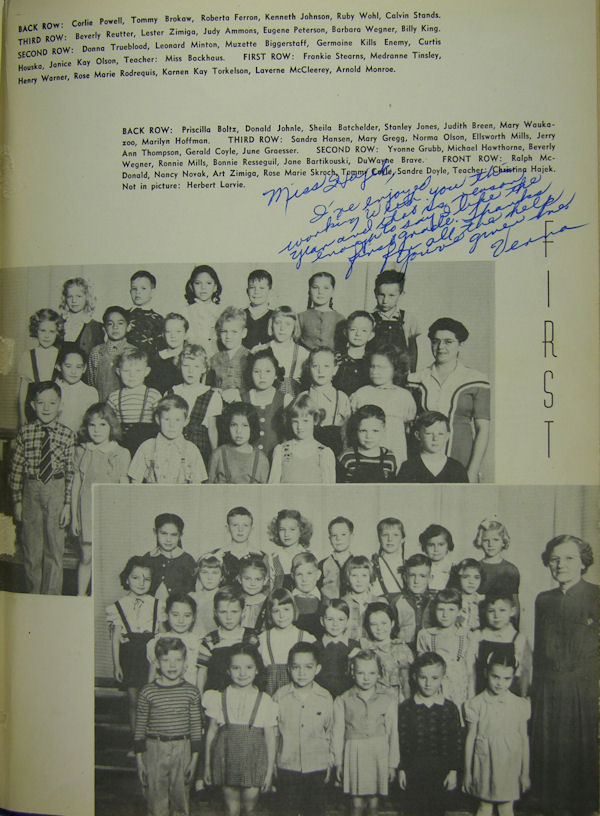

class pictures from yearbooks