Archie described himself as a Phi Beta Kappa gone bad. He was at Igloo during the early years, 1942 to 1949. He was an interesting character.

"Gilfillan authored one of the funniest and most introspective works on early 20th-century West River life." -- South Dakota Magazine

"Sheep"

| BHODian | page 42 | April 1945 |

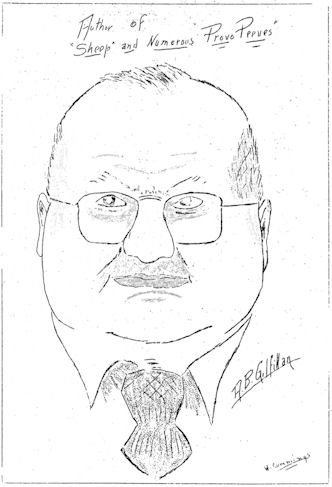

The Arts have been and are well represented among the BHODians. Of the many talented people, whether in music, drama, art or writing who are making Igloo their home for the duration, one of the best known on the depot is Archer B. Gilfillan, Phi Beta Kappa, bibliophile, philosopher, author and last but not least, editor of the Igloo Magazine. "Archie" as he is known to his many friends, has been the guiding light of our magazine since the days of the "Provo Peeper" and by his untiring devotion has carried our publication through many trying times.

| Vol. 1 No. 18 | page 3 | May 9, 1952 |

I reached Provo late one afternoon - August 25, 1942. It was so huge a place that it took men an hour to find the building where I was supposed to report. After that the first considerations were food and a place to sleep. I went to the commissary and drew my bedding; then I found the barracks to which I was assigned - and got my first real jolt. After the luxury of two years of rooming alone, I found that I had suddenly acquired forty-five roommates. I also found that my cot was the seventh from the door in the left-hand row on the second floor of the fifth barracks in the second barracks row. It took a knowledge of higher mathematics plus a good memory to go to bed successfully at Provo.

I had heard various things about the food at Provo, and I can only say that after five years of eating in a cafe attached to a hotel, I still like the food here. For breakfast the morning after I arrived we had cereal, bacon and eggs, bread and coffee. That kind of a meal would cost fifty-five cents at restaurant prices and I have never been able to afford that much for breakfast. There is no question of "seconds" here. The food is served "country style" and you can have as much of anything as you wish. The meals are thirty cents straight, and only because they are served in such immense quantities can they be of such high quality. For one meal, at the peak, four thousand customers were served. Last Sunday I went to a neighboring town and paid seventy-five cents for a dinner that did not compare with what I would have had at camp. Nor is there any monotony in the meals. Each one is different and all are well cooked.

The four immense mess halls, each seating from eight to twelve hundred, jut out from the kitchen like the spokes of a wheel. When one mess hall has filled, the doors are locked - no fooling with this outfit - and the steady stream of customers is directed into the next one; which, when filled, is locked in turn. By the time the first mess hall is reached again, the tables have been reset and all is ready for business.

Did you ever see a library where 98 percent of the patrons are men, and 90 percent of these keep their hats on while they read? Where there are no "quiet" signs and where the patrons smoke cigarettes, cigars or deadly pipes according to their whim; and where the personable librarian behind the desk joins them in a cigarette, perhaps because she simply enjoys a smoke? In this library the patrons read or talk as they choose. Several checker games are in progress, and at another table a brainier pair are engaged in a battle of chess. The other day a dog-fight took place in the library. This was too much for even the broadminded librarian, and she requested one of the men to remove his dog. "Why, ma'am," he protested, "it was the other dog that started it. If either of them is to be put out, he ought to be the one." That ended the argument.

If this place had a motto, it should be "They do things differently at Provo." For here, when a man wishes to take a bath, he doesn't ask whether there is any hot water but whether there is any cold water. For the amount of cold water govens the length of his bath, because the un-cooled water, coming out of the ground at a temperature of 140 degrees, would take the hide off a large-sized rhinoceros. Where most places install an elaborate heating system to render the water agreeable to the human body, Provo is to have a cooling system with the same object in view. A provo shoe shine consists of elbow grease and some of the aforsaid hot water, which is the only combination tough enough to get the best of Provo mud.

When this country was first settled, the Yankees colonized New England; a the Dutch, New York; the Spaniards, the Southwest; and the French, Louisiana. Contacts between the groups were few and assimiliation slow. Here at Provo the process has been a much more violent one. Six thousand men, representing three races and thirty or more nationalities, were dumped on the barren prairie south of the Black Hills and told to get along together. And the miracle of it is that they do get along. The Sioux seek the metaphorical scalps of their ancient enemies at checkers, ping pong or cribbage. "God's Chillun" entertain the rest with inimitable gifts of song and dancing. Men of a score of nationalities, or of none, argue interminably but amicably the perpetual questions of war and politics. On only two points do they agree - their Americanism and their patriotism. These perhaps form the tie which binds such diverse elements together.

However, this diversity is not one of nationality alone but includes almost every occupation, and every division of the economic scale - teachers and students, both high school and college; skilled artisans and day laborers; ex-theologians and prison guards; truck drivers and saloonkeepers; photographers and butchers; ranchers, farmers and farm-hands; and professional followers of construction camps. The above list includes only those of whom I have personal knowledge. The list could be expanded several times. I even met a fellow sheepherder.

Among the women and girls at Provo there is as much diversity as there is among the men. For in this old maid's paradise are girls of every type - beautiful, pretty, cute, plain, homely and drab. There are college and high school students; brainy executives and mannequins; nurses, both practical and professional; secretaries and typists; waitresses and commissary clerks. There are farm women and city women; widows, grass and sod; grey - haired grandmothers, matrons and young girls; eager-eyed youth and disillusioned age.

Then there is the problem of badge pictures. When I first saw the alleged likness on my badge, I realized that I had a secret enemy in the Bureau of Indentification. I could have used that badge as a one-way passport into any penitentiary in the country. On presenting it a the gates, I would inevitably have been slapped into murderers' row, pending the receipt of fuller information. I realized that the photographer didn't have very much to work with, but I didn't think that was sufficient excuse for representing me as Public Enemy No. 1. Some time ago I was talking with a woman who had just received her badge. She didn't have much to go on either. She said to me, "If I thought I really looked like that, I'd go out and hang myself." And she spoke as if she meant it. A commercial photographer who turned out work like that would speedily starve to death. Unless, as is more likely, he first became the subject of mob violence. It would seem that there should be some way of respresenting us as the normal men and women that we are, rather than making us look like members of the graduating class of dear old Alcatraz.

| Vol. 1 No. 18 | page 9 | May 9, 1952 |

Several people have asked me why I do not write an article on Provo mud. There are several reasons why I cannot do so. In the first place, after probing the resources of a somewhat large vocabulary, strengthened and enriched by several years of expostulation with the sheep, I find I simply do not have the command of language necessary to describe the above mentioned natural phenonmenon. Futhermore, even such poor subsitute words as I could enlist would inevitably melt down the keys of the typewriter, or set the manuscript afire, or result in barring the otherwise high-class publication from the United States mails.

For we are talking of Provo mud, the mud that sticketh closer than a brother - closer, in fact, than anything else in the world except another piece of Provo mud. The man who first conceives the idea of bottling this mud and selling it under the trade name of "Provo Glue" will clean up a million, besides increasing the life expectancy of various aged horses and cows, whose horns and hoofs are at present covetously regarded by the manufactures of commercial glue.

When it rains at Provo, people pack around enough mud with them to make them taxable property. More transfers in real estate take place than during a land boom. Somebody is always transporting real estate from the place where it always was to some other place; but it really doesn't make much difference, because someone else always steps right in it and takes it back again. People creep cautiously to and fro with their fingers crossed, for in very wet weather it is still possible to do the splits ten feet inside the door of the recreation building. I have previously mentioned the courteous manners generally prevail throughout the project. But there is one place where this does not apply, and that is on the half-mile stretch between the main crossroads and the store after a rain. The unlucky pedestrian along this peice of road is in constant danger of a shower of mud from passing cars. Some of the cars, it is true, slow down as they pass and do him no damage; but others hustle by and present him with a mud pack from the ears down. The poor pedestrian does not have much choice in the matter. He can either stick to the highway and risk a mud bath, or he can leave the road and wade through the landscape up to his neck. Now I don't wish these mud-slinging drivers the bad luck they deserve, because to do so would be uncharitable. All I hope is that after the next rain, they will slide gently into the nearest convenient ditch, and have nothing to do for the next three days but sit there and think about the people they have needlessly splashed mud on.

Edgemont Tribune; circa 1950; Archer B. Gilfillan, of Deadwood, S. D., is spending several days in Edgemont visiting in the home of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Forman. Mr.Gilfillan was formerly employed at Igloo, and was the editor of the Igloo magazine which at one time was published in Igloo. Before leaving, Mr. Gilfillan will also visit Mr. and Mrs. Howard Brigham at Igloo. He is now busy writing a book on "South Dakota", in which he will include a tribute to Cpl. Kenneth Forman, who lost his life in service in Korea. While in Edgemont Mr. Gilfillan favored the Tribune office with a friendly call.

The Edgemont Tribune; Feb. 21, 1945; Word has been received from Archer Gilfillan that he is enjoying his leave at Denver, Colo. Archer has been editor of Igloo Magazine since its inception and we of the Service Branch are missing his service at this time. We hope that Archer, who spent 20 years of his life looking down upon sheep, will not sunburn the roof of his mouth looking at the skyscrapers while in Denver.

The Edgemont Tribune; March 7, 1945; On Saturday of last week, Archer B. Gilfillan of Special Service was much surprised, not to say overwhelmed, when his office mates produced a delicious birthday cake, his birthday being the next day. The cake was tactfully decorated with one candle, although the recipient admitted to being 36, later (under pressure) to "at least 36". It is a wonderful experience for an "old bach" to be remembered on an anniversary which is getting rather too high numerically.

Alma Birnbaum worked with the IBM machines and states that Archie worked in that department also.

Archie Gilfillan was South Dakota's sagebrush philosopher. His prairie wit entertained people in the ranching areas of Montana, North Dakota, Wyoming and South Dakota through the Great Depression.

He talked at colleges, high schools, livestock conventions and smoky bar rooms, giving neighbors and friends a chuckle or two during hard times. Public speaking seems an unlikely sideline for a man who spent 20 years as a lonely sheepherder in northwest South Dakota.

Perhaps even more ironic, however, is the fact that Gilfillan authored one of the funniest and most introspective works on early 20th century West River life. Sheep: Life on the South Dakota Range remains in print even today. Stories from the book are told and retold, especially in the bar rooms and kitchen tables of Harding County where he spent his sheepherding days.

Archer Gilfillan was born Feb. 25, 1886, in White Earth, Minn., where his father served as an Episcopal missionary. In 1898 the family moved to Washington, D.C., after Archie's father suffered a nervous and physical breakdown.

During his teenage summers, Archie worked on farms in Virginia, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. He grew to like the farm animals, especially sheep. He claimed to have bought a sheep for $3 when he was a youngster and the animal was sold for $6, along with the wool, just one year later. He invested the $6 in three more ewes and sold them for $18.

Years later he wrote, "While I had never been especially good at mathematics, it seemed to me that 100 percent a year was a pretty good return on an investment and that if I could keep it up regularly I ought to be worth quite a bit some day. So I bought as many ewes as I had money for, and left them, supposedly, on shares, with a neighboring farm woman who had a few sheep of her own."

But the woman mailed him a check for just $10, claiming the pasture bill ate up the rest of his investment. "I learned about women from her," he wrote. "I was wiped out. But while women are men's ineradicable weakness, sheep are not; and it was many a year before I again took up the trail of the Golden Hoof."

He started high school in 1902, two years late because he suffered from typhoid fever and traveled Europe for two years with two aunts while he recovered.

He wore glasses and was short and stout. Sensitive about his height and roly-poly appearance, he avoided sports. An inferiority complex seemed to haunt him all his life, but he maintained a friendly, goodnatured personality.

Archie graduated from high school in 1906 as an honor student. He started at Amherst College but transferred to the University of Pennsylvania at Philadelphia. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa with an emphasis in Latin and Greek in 1910. Archie enjoyed debate and excelled in most of his courses.

After graduation he followed his dream west to South Dakota where he worked on a ranch near the Black Hills. Big cattle ranches of the free grass era had just gone out of business and little people with big dreams were arriving to homestead. Archie caught the "free land" bug and decided to homestead in Harding County near Slim Buttes. He raised sheep but never seemed to find the rhythm of buying low and selling high. In three years he gave up ranching and decided to follow in the ministerial footsteps of his father and grandfather.

For three years he attended Western Theological Seminary in Chicago, an Episcopalian institution. On the day before graduation he had a change of heart and dropped out of school to join the Catholic Church.

(photo of Archie's wagon)Gilfillan's sheepherder's wagon is now on exhibit at the Dakota Discovery Museum in Mitchell.

Archie returned to Harding County. For two years he herded sheep on ranches with small flocks. In 1916 he hired out to Almon "Al" Dean and herded sheep for him until 1932.

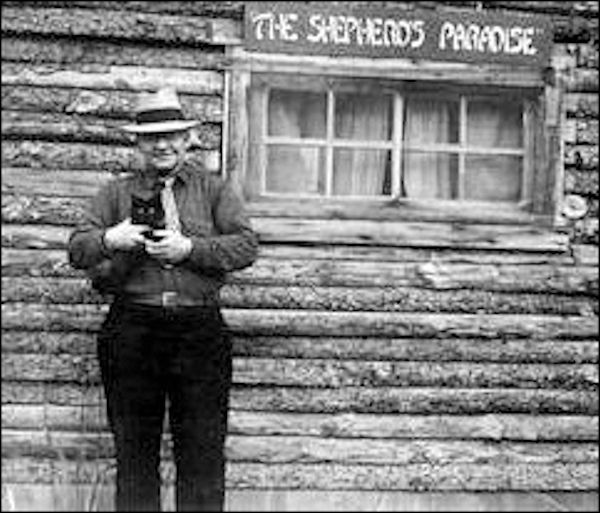

During those 16 years, Gilfillan developed a problem with alcohol. When Dean caught him in a wagon drunk, he moved him to the home ranch to do chores. Such confined quarters were un-bearable to Archie and he took another herding job at a neighbor's ranch in the spring of 1933. He soon retired from the sheep business and rented a log cabin in Spearfish. He named the cabin Shepherd's Paradise.

He had kept a diary in cipher, a system of secret writing based on a key, for eight years and four months starting in December of 1924 when he was 38. During those years he filled 9,010 pages of standard letter-size paper.

The diary was later transcribed by John Jenson, rare book librarian at the University of Minnesota, after Emily Heilman, Archie's sister, donated the work to the university.

Gilfillan claimed that he never failed to make a daily entry in his diary but some days are missing. Perhaps the wind grabbed a page occasionally when the sheep wagon door opened. Some of the jottings were reportedly not meant for public consumption because they contained juicy gossip about the pioneering families of the northwest.

Information from the diary filled the pages of his book Sheep, which was published in 1929 by Little and Brown Co. after being rejected by several other publishers. It sold for $2.50. Gilfillan received 10 percent and he voiced the writer's lament that the publisher gets 80 percent while the writer gets peanuts.

Gilfillan said his first royalty check should have been about $600 but he gave away too many books so the publisher sub tracted $200.

In his diary, he was extremely frank about his day-to-day life. His book reveals a sheepherder's western humor and philosophy that can only be fully appreciated by readers who understands sheep or people.

He never stopped learning, and he devoured books. At one time, he subscribed to 15 magazines and claimed to have a library of 500 books. "Even if a herder does not particularly care for reading, he will be driven to it in self-defense," he wrote.

Reading was more than a pastime, he quipped. "If the herder on an intensely cold day can get interested in a good story, it will serve to take his mind off his other troubles, such as how much colder his feet will have to get before they crack and break off, and whether the sun is really standing still, or whether that is merely an optical illusion."

Gilfillan wrote in an earthy, irreverent style. He detested arrogance in writing or talking. In reference to Mary Austin's book, The Flock, he said that she never used a word in its right meaning if she could distort another to take its place. Of course while writing a book about sheep it would be impossible to avoid profanity. If it answered a question or released pent up frustration, Archie could curse but he never condoned vulgarity in any form.

Sheep was reprinted in 1930, 1936, and 1956 and 1957. Gilfillan complained that he never did find out how many copies were sold in the first two printings. In recent years, it has been reprinted by the Minnesota Historical Society Press.

During his years as a sheepherder, Gilfillan suffered many hardships including lightning, cloud bursts, floods, blizzards, rattlesnakes, wolves, coyotes and two-legged camp robbers. Once, as a tornado approached, he was forced to seek shelter in an old well.

Gilfillan had other challenges in life. Card games, especially poker, were his downfall. He liked to socialize and always found an excuse for a drink. Unfortunately, he never seemed to realize that cards and whiskey did not mix. Al Dean let him borrow on future wages to pay off his debts and the Ivy League sheepherder was always overdrawn.

In 1924 Gilfillan gave a talk to the Woolgrowers Association at Helena, Montana. He caught everyone by surprise with an outstanding, well-informed speech he called The Secret Sorrows of a Sheepherder. He never gave his name so he remained unknown for several years in spite of efforts in Montana to identify him.

His three secret sorrows were sheepmen who didn't know as much about sheep as the herder, cowboys who got all the glory while the sheepherder was looked down upon, and women who wanted to be substitute sheepherders.

He maintained that women were ill-equipped for the occupation. "The truth is that in many respects they are unsuited to the work," he wrote. "With no more than a discreet allusion to the three quickest means of communication, can you really picture a woman engaging in an occupation which would leave her more or less in the dark with regard to the doings of even her immediate neighbors?"

Language would be an even bigger problem, he thought. "There are frequent occasions in herding when the feelings seethe in the herder's bosom like white-hot steam in an engine boiler. His anguish finds vent in language that he has picked up at odd times around garages, stables, poker games and from autoists who were changing tires. Women, not having frequented these places, would be at a distinct disadvantage."

Gilfillan liked women. He just didn't think they should be sheepherders. But he disdained cowboys. "Is there any intrinsic reason why the man who takes care of cattle should be a romantic, half-mythical figure, while the man who takes care of sheep is either a joke or anathema?" he wrote in Sheep.

Gilfillan argued that the sheepherder was superior to the cowboy because he was his own boss most of the time while the cowboy "may be able to carry more than one day's orders in his head, but he seldom has the opportunity of proving it."

In spite of that, he acknowledged that, "every kid in the range country looks forward to the day when he can get hold of hair pants, a ten-gallon hat, a Miles City saddle and a pair of big spurs, and then cultivate a bow-legged walk and hire out to a cattleman."

Gilfillan gave a commencement address at Buffalo on May 22, 1930, and the graduating seniors enjoyed his sharp, western wit. He quipped, "I have the suspicion that Prof. Chanson has asked me to appear before these graduates to serve as a warning, so that they can see what may happen to them if they do not watch their step and be just a little bit careful."

The herder-author often referred to himself as a Phi Beta Kappa gone wrong. The Gilfillans were a literary family. Archie's grandfather wrote The Origin of Sin. He surmised that it was not a commercial success because people are more interested in their daily practice of sin than finding its origin.

Archie's father, a minister like his grandfather, wrote an unsuccessful book trying to restrain people from seeking what they wanted. S.C. Gilfillan, Archie's brother, wrote books, too, and his nieces also enjoyed writing.

At Spearfish, Gilfillan became a freelance writer for several South Dakota newspapers but money was scarce. In 1936 he published A Shepherd's Holiday. It was 52 stories collected from his newspaper articles and published at Custer.

Late in life, he also authored A Goat's Eye View of the Black Hills, with assistance from longtime friend Hoadley Dean of Rapid City. He retold many legends of the South Dakota mountain towns, adding his personal perspectives and a big dose of his dry humor.

He also explained in the book why he remained a bachelor. "You profess sincere and unbounded admiration for the beauties of the opposite sex and you practically lay your heart at their collective feet; and then you meet some individual who combines the poorer qualities of a mama wildcat and a bitch wolf, with a voice like a buzz saw, the temper of a slapped hornet, and a disposition that would curdle the milk in four adjoining counties. And then you have to revise your opinion of the sex all over again -- and downward." In short, he never met a woman he liked who would have him as a husband.

The Great Depression spread across South Dakota before local writers heard about the Federal Writer's Project (FWP) being promoted by Eleanor Roosevelt. Unemployed writers were hired to interview old-timers, search files and records, collect folklore, and preserve the history, culture and contemporary life of American communities.

The project was considered a work program and no one expected it to produce anything of lasting value. Today, the books and material these men gathered and wrote are valuable treasures. M. Lisle Reese, a talented Montana native, was hired as director of South Dakota's Federal Writers Project and he hired Gilfillan as his assistant.

He stayed until the project ended in the spring of 1942. For the next seven years he worked at the Black Hills Ordinance Depot at Provo (Igloo). He wrote for the Igloo Magazine, did clerical work and served as librarian. When that job ended in 1949 he moved to Deadwood. In failing health, he lived in retirement.

When Gilfillan retired to Deadwood, he stayed at the Wagner Hotel. He usually sat on a straight back chair and read a book or walked along Deadwood streets, visiting with his neighbors.

While enjoying a walk on December 17, 1955, he dropped to the sidewalk. He had moved on to greener pastures.

Family and friends buried the old sheepherder at Belle Fourche. But Gilfillan's bad luck continued even in death. They buried him beside two great cowboys, Paul Bernard and Joe LaFlamme.

EDITOR'S NOTE - This story is revised from the Nov/Dec 1996 issue of South Dakota Magazine. Paul Hennessey was teacher, and also worked as a private investigator on the West Coast. Hennessey knew Archer Gilfillan during the sheepherder's years at Igloo.

Two of South Dakota's favorite adopted sons had more in common than either probably realized, and though their paths undoubtedly crossed several times, it is very possible that neither considered the coincidences at the time.

Charles Badger Clark, Jr., was born in Iowa in 1883. He was the son of a Methodist meinister, and reportedly at one time thought about entering the ministry. Archer Gilfillan was born in Minnesora in 1887, was the son of an Episcopalian missionary and spent some time in the seminary.

Both were avowed bachelors, but it didn't start out that way. Badger Clark, in fact, was engaged to the same girl, Helen Fowler, twice. They didn't fight, really, but Badger dragged his feet for several years and Helen got a better deal elsewhere. Gilfillan never claimed to be celibate, but he just couldn't commit. Both men claimed to appreciate womanhood from a distance on a regular basis, but they did the safe thing - they just wrote about it.

When Clark's hijinks got him kicked out of Dakota Wesleyan University in 1903, he worked on a cattle ranch in Arizona, arriving by way of Cuba. Gilfillan's episodes of hilarity drove him to the sheep ranges of the Black Hills and thereabouts. Badger Clarks's first poem was published in The Pacific Monthly; Gilfillan was published in The Atlantic Monthly. (That seems quite fitting, actually, since cattle and sheep men were about as far apart in those days as the Atlantic and Pacific.)

But here they were in South Dakota, contemporaries. Gilfillan schmozed around the Southern Hills for awhile and ended up in Deadwood. Clark started out in Deadwood and ended up in the Southern Hills. Both left many stories about how it was at the time.

A personal favorite takes place in Lead, which Gilfillan seemed to single out a lot. In his book, "A Goat's Eye View of the Black Hills," Gilfillan relates the tidbit about Lead's streets called "Ups and Downs in Lead," where he asks to hitch a ride downtown with a grocery delivery man. The man agrees, but says Gilfillan will have to ride along for a few stops along the way, Gilfillan agrees.

"We hadn't gone very far before he turned in to, or rather against, a street that led apparently straight up. I wouldn't say that it was exactly perpendicular, but I noticed that they had to tilt the telephone poles outward, so that the crossarms wouldn't dig holes in the street," he wrote.

Gilfillan asked the man if he really intended to go on up, and the man assured him there was nothing to fear." ... he stopped at a curb a half a block up," the nervous passenger recalled, "and this cheerful maniac went whistling into the house, leaving the engine running and only the brake on."

Gilfillan further related his peril:

"So I lay there on my back on the back rest of the seat, with my feet in the air, looking up through the windshield, which was just a few inches above my face ... and all the time the only thing between me and eternity was a strip or two of asbestos that, under the abnormal strain, might decide to part company at any time."

Everything turned out all right. The driver knew his neighborhood and backed the car down. Gilfillan must have been relieved; he summed up the experience by saying, "If we had tried to turn around, the car would have gone over and over like a tumbleweed and delivered groceries all the way to Main Street. ... If there is one thing reasonably certain, it is that deliverymen in Lead can't get life insurance, not if they tell the truth, anyway."

Gilfillan's "other life" of nearly two decades as a sheepgerder is even more wild an wooly. Badger Clark gave up his wild and wooly ranch life for a more sedate lifestyle in the secluded beauty of Custer State Park. He built his log cabin, dubbed the "Badger Hole," in 1924, he loved the outdoors and lived off the land. If memory serves right, he didn't drive or own a car, but at any rate, he did not consider it important to his existence.

In 1937, Clark became South Dakota's first poet laureate, although he preferred to keep the Western image and good-naturedly called himself the "Poet Lariat." He made a small living for himslf by giving lectures throughout the Black Hills and was a popular invited guest at many functions.

Clark gave the graduation address at Keystone for many years, and also was frequently a preacher at Keystone's Congregational Church. His most famous work, "The Cowboy's Prayer," has been reprinted perhaps thousands of times over the years, but it was often credited as "author unknown," so this classic piece of Western American, whose residuals could have provided a comfortable cushion in old age, made others rich instead.

Not that either Badger Clark or Archer Gilfillan wanted fame or fortune. Both men seemed to find their riches in what life had to offer and enjoyed this to its fullest. These colorful characters put pen to paper and left a wonderful legacy of Black Hills history.

Bev Pechan, director of the Old Fort Meade Cavalry Museum, is a freelance writer with a long-time interest in regional and frontier history. She lives in Keystone.

South Dakota Hall of Fame

Archer Gilfillan from White Earth MN

Inducted in 1979

Category: Arts and Humanities

DOB: 1886

POB: Unknown

DOD: December, 1955

Buried at: Unknown

Archer Gilfillan was born in 1886 at White Earth, MN, where his father was an Episcopal missionary on the Indian reservation. His family moved east when Archer was about 14 years old. His parents sent him to private military school and later to Dartmouth. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvannia, majoring in Greek and Latin. He then entered an Episcopal seminary, and his family and he felt he would follow in his father's footsteps. A few months before graduation from the seminary, Archer became a convert to Roman Catholicism. After the trauma of this abroupt change in religious philosophy, which also meant a change in his life's ambition, he headed west "to think things over". He homesteaded near the post office of Murchison, and with a $10,000 stake from his father, bought a band of sheep with the disire of becoming a rancher. He had absolutely no experience with money or men. The result of this inexperience caused his ranching venture to go broke.

He drifted into Buffalo, SD, in 1910 where Al Dean, who owned and operated a sheep ranch, took him home and put him to work. He shepherded at the Al Dean ranch for 16 years where he lived in the compact interior of a sheep wagon. During this time, he wrote articles for the Saturday Evening Post, Atlantic Monthly, Collier's and Farm and Fireside.

He ordered a portable typwriter from the mail order catalogue and taught himself to use it. At night in his sheep wagon, he wrote "Sheep", which has been acclaimed as one of the finest South Dakota books ever written. It was a best seller in the 20's and 30's and is classed as one of the finest examples of writing of the generation.

Gilfillan left Dean in 1933 and, after a period of writing at Spearfish, he joined the Federal Writers Project where he assisted in the publication of the South Dakota Guidebook and another on Place Names. During this period he wrote a regular column for several newspapers including the Aberdeen American-News. In 1942 he joined the Black Hills Ordnance Depot staff at Igloo where he worked in special services and edited the depot newspapers, a position he held until about 1951 when he moved to Deadwood.

After moving to Deadwood, Gilfillan wrote and produced "A Goat's Eye View of the Black Hills." In his later years in Deadwood, he completely recatalogued the public library. He lived in te Franklin Hotel and there he wrote letters each morning. Each afternoon he would assist the public librarian. He passed away in December of 1955 late one afternoon while returning from the library.