| Walrus | Pg. 3 | August 13, 1954 |

You all know Joe, your genial Chief of Police, but there may be a few things you don't know about this handsome hunk of man. (No insinuation intended the he might be a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde!)

Did you know, for instance, that he has lived in this part of the country most of his life, as did his father and grandfather before him? In fact, Joe as a little fellow, had his first glimpse of the Black Hills peering from the back of a covered wagon. His father has the distinction of being the first white child to be born at Fort Yates. His grandfather was with General Custer's command and made history as he was detailed on wagon trains at the time of the Custer massacre.

It is obvious that Mr. Marsh has always liked to live, and live dangerously. His diversified activities all indicate he prefers "taking a chance" to a safe, humdrum existence.

He became actively intersted in boxing and became the state Golden Glove champion in 1933. Did you know that he was at one time a top cow hand and bronc buster in the northwestern part of the state? He participated in bronc and steer riding, roping and bull dogging and entered many rodeos including the Belle Fourche Roundup.

And did you know Mr. Marsh was at one time a lineman for the Black Hills Power and Light Company and that he helped build a number of the high lines in the hills. On a job at Sheridan Lake, a new somewhat inexperienced man was up the seventy foot pole with Joe.

His climbing hooks broke out and he would have plunged to a certain death on the jagged rocks below but for the bravery, quick thinking, and strength of Joe who manually held him until the young fellow could right himself.

Gold mining is another dangerous occupation to which our Mr. Marsh at one time applied himself. He assisted in extricating the bodies of two men in a mine disaster at Hill City. The fact that the men were his friends didn't make the job any easier.

His work as law enforcing officer including two years as Chief of Police of Custer and special deputy of Custer County and two years as marshall of Corson County as well as the twelve years as Chief of Police at BHOD represents many close calls. There was the time two violent characters managed to get possession of Joe's gun while being placed under arrest. He had to battle with both of these desperate men who felt they had nothing to lose, single handed to retrieve his weapon. Thanks to his agility and strength, no blood was spilled.

And, did you know that Mr. Marsh "went to the dogs" in 1946? At that time he became seriously interested in raising and training dogs, and has through the years succeeded in capturing many coveted prizes with his animals. A perfect understanding seems to exist between these not dumb creatures and their master - they respond to his kind treatment and training and give everything they have.

Be it Joe or "the other Mr. Marsh", we can have confindence that the security of our community is in capable hands.

| Walrus | Pg. 3 | Sept. 16, 1955 |

Police Chief, Joe B. Marsh made the sports page of the Billings Gazette recently when he jouneyed there to serve as judge in the Montana Retriever Club field trials.

Marsh was one of the three judges which participated in the trials which drew dogs from Wyoming, Idaho, South Dakota, California and Washington.

Judges for such events are chosen for their knowledge of field events and abitlity to recognize the outstanding ability of a dog.

| The Trader | Pgs. 1, 4, 5 and 6 | March, 1981 |

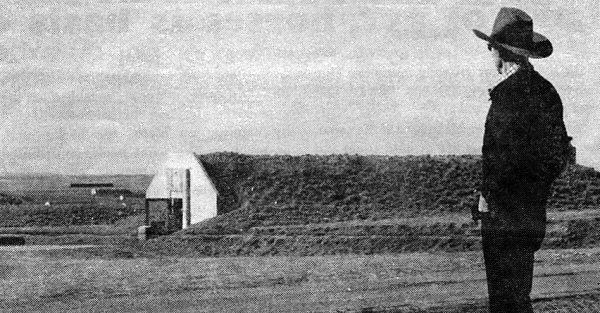

RETURNING TO IGLOO 14 years after he left, Joe Marsh notes

that while the depot countryside looks similar, the igloos now

house sheep and hogs rather than bombs and ammunition.

At 71, Joe Marsh is tall and trim, and western-cut clothes look as though they were made just for him. He carries himself with authority, but there is little egotism in his self-assurance. His strong hands that once pounded out boxing victories can also create music. He might well have served as the original model for the Marlboro man, except that being a symbol for a tobacco product would be out of place for a man who does not smoke, drink, or swear.

Joe's roots are deep in Dakota Territory history. Joseph B. Marsh, his grandfather, rode with the 7th Cavalry and came into the Black Hills with the Custer expedition in 1874. Two years later, when the 7th Cavalry went up against Crazy Horse at the Little Big Horn, Joseph was assigned to an escort detail with a wagon train traveling from Deadwood to Ft. Lincoln (North Dakota) and thus escaped the massacre. Joseph's son, Joe's father, later became the first white child born at Ft. Yates (North Dakota).

Joe and the western half of the Dakota Territory grew up together. Reared at military posts along the North-South Dakota border, Joe experienced an early life that was a mixture of cowboy-Indian-soldier influences. At times he attended school on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, learning to speak Sioux in order to communicate with his classmates. By the time he was nine, he was a "hand", helping trail a herd of army remount horses to Montana.

Growing naturally into riding and ranching, Joe rode a year for the Diamond A Cattle Company, an outfit so large it grazed livestock along 100 miles of land bordering the Cheyenne and Missouri rivers. "There were 20 different cattle camps on the spread," explains Joe in emphasizing the ranch's size.

He also tried his skills at rodeoing. While saddle broncs were his main event, he sometimes rode bulls. "They were so stout," comments Joe, "it was just like riding a freight train." For years the Belle Fourche Roundup used posters with a picture of Joe. "It was a good picture," says Joe, "but I was bucking off."

Joe's young life was not all rough and tough, however. The Marsh family, including Joe's four sisters and three brothers, literally made music together, playing as a family band at local barn dances. Joe's primary instrument was hoedown fiddle - which he still plays - but he once filled in for two nights as a drummer with the Lawrence Welk band at a rodeo appearance in a small northern South Dakota community.

His closeness to his family is what eventually got Joe to the Black Hills. His sister was sent to Sanator to recuperate from tuberculosis. "She was so lonely she just wasn't making any progress," recalls Joe sadly, "so I moved down to be near her. It worked, too," he happily adds.

While visiting his sister at Sanator, he met a young lady patient who was to become his wife. Following their marriage, they returned to North Dakota. Apparently, as Joe solemnly recalls, his wife's case of tuberculosis had not been completely arrested, and following their daughter's birth, his wife died. He later returned to the Hills and eventually married his present wife Claudia, a "Southern belle" who had come to Sanator as a nursing student.

Making a living was not easy in the early 1930's and like many other young men, Joe had joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, working as a forester in various Black Hills CCC camps. He helped put in Stockade Lake east of Custer and tells how the government figured it would take a couple of years for the lake to fill and the water to begin going over the spillway. "One night (during the first year) it rained," recalls Joe with a grin, "the lake filled up, the water went over, and Camp Dorin (the CCC camp built right below the dam) almost got washed completely away!" Now, years later, Joe works on the restoration committee for Stockade Lake.

"I don't mean to brag," Joe says about his boxing career, "but I never lost a fight." In 1933 he won the South Dakota Golden Gloves Heavyweight Championship, and in 1935 while in the CCC he won the Seventh Corps Area (five states) championship. "Competition was tough, too," Joe explains. "There were a lot of young men and they didn't have much to do but fight."

Joe knocked out all but one of his boxing opponents and that win was a technical knockout (stopped by the referee) in the state Golden Gloves. As Joe was leaving the arena after that fight, he saw his opponent sitting alone and dazed in the dressing room. "I showered him, dressed him, and took him to the hotel and bought him dinner," Joe recalls. Years later he came upon the same fellow cutting timber near Tigerville. "He remembered me," says Joe with a smile.

After the CCC, Joe worked at a variety of jobs. "I got experience in everything," says Joe. "When someone asked, I could say, 'Yes, I can do the job.'" He worked for a while as a miner in the Silver Slipper mine near Hill City. "Can you imagine ore that would assay at $20,000 (at $34 an ounce) a ton!" Joe recalls with a glint in his eyes. "Once I plugged the drill steel with solid gold!" Tears come to his eyes when he recalls the cave-in that killed two of his co-workers. "My wife said my mining days were over," explains Joe. "We were about to have a baby and I didn't want to worry her so I quit."

Joe did not, however, settle for many "safe" jobs. "I bet I've climbed every pole in this town (Custer)," says Joe about his work with an electric power company. Eventually, though, it was his strength and prowess with his fists that got Joe into law enforcement, something that he is still actively involved in although he is officially retired.

For almost three years he served as a deputy sheriff and chief of police for Custer. "There were only two of us then," explains Joe, "so whoever was on duty was Chief of Police." He ran for sheriff, but withdrew from the race to take a job as a guard at Igloo in early 1942.

Igloo, officially known as the Black Hills Ordnance depot, was established south of Edgemont by the government as a military weapons and ammunition storage post in April, 1942, just four months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Six months after he started work, Joe was made Chief Guard. When the U.S. Army took over the base a few years later, Joe became Provost Marshal of the post, one of only two civilians to hold such a position at military installations. The government gave him special training in security and intelligence work, but much of Joe's success then and later seemed to depend on the physical. With no-nonsence authority he says, "We didn't put up with trouble makers."

Claudia served as a nurse at the post hospital, later becoming director of nursing and supervisor of surgery and obstetrics. For most of the 25 years that they worked at Igloo, they lived on the post, but during the last seven years they commuted from their ranch south of Custer.

Just insuring post security was critical at Igloo. "We had about 21 miles of perimeter we had to patrol," explains Joe, and it took a security force of 200 men to do the job. One section of the base stored ammunition in Standard Above Ground Magazines, a series of brick buildings. Another section of "igloos" and "turkey sheds" stored other ammunition and bombs, including those containing poisonous gases. Igloo also had the additional security problems associated with being a POW camp for Italian soldiers.

During his years at Igloo, Joe was awarded the "Gold Medal," given by the U.S. Government to a civilian for outstanding service, in this case bravery. Following the explosion of an Igloo, Joe entered the area to search for survivors even though there was danger of live ammunition continuing to explode. Two men had been killed, but under the rubble of cement, steel, and dirt one survivor was found.

FOLLOWING THE EXPLOSION of an igloo, Joe entered the area to search for survivors and won a medal for bravery.

"His heavy coat had literally been blown off him," remembers Joe, "and his vest was peppered with little holes, but he really wasn't even hurt."

"What I remember," adds Claudia, who was on duty at the hospital, "was cleaning all the dirt out of his ears. They were just packed with dirt!"

LOOKING AT JOE'S GOLD MEDAL for bravery while reminiscing about their days at Black Hills Ordnance Depot at Igloo are Claudia and Joe Marsh.

Joe found that this area was really a part of the "Old West" when it came to law enforcement. When he was in uniform they challenged him to see if he was really tough without a gun and badge. "You had to be tough," says Joe matter-of-factly. "Everyone picked fights."

"One night," says Joe. "I went into the Coffee Cup to eat and a fellow started right in talking about how he didn't like uniforms. He was served a sizzling steak and he smashed the platter on the counter and came at me with a broken chunk. Of course, he was drunk." Joe easily subdued his attacker by clamping an "iron claw" on the man's wrist, and then led him meekly off to jail before returning to eat his own supper.

On another occasion Joe noticed a crowd forming in front of another Custer cafe. A large drunk Marine who had been raising havoc inside the cafe was challenging Custer sheriff Gus Carlson to try to load him in a squad car. "The back door of the car was open," recalls Joe, and I just ran headlong into that Marine, hitting him in the back and sending him sprawling into the car. I told Gus to hurry and close the door. He said he couldn't because the guy's feet were sticking out, and I said, "That's all right, close it anyway!"

To get away from the strains of law enforcement, Joe worked with dogs, training them in both obedience and field trials. He considered it a hobby, but occasionally he worked with a dog on the professional level. Over the years, he won many field trials in South Dakota and neighboring states. Of all the breeds he has worked with, he favors the black Labrador and the German Shepherd, but he also has good things to say about Golden Retrievers.

KEEPING THEIR EYES on a bird during a field trial are hunting dogs and their handlers, including Joe Marsh (right) and the late Wilbur Goode (left), father of Pam (Mrs. Jim) Kemp of Custer.

While at Igloo, he learned to fly and for many years owned his own plane. Only in recent years has he let his private license lapse.

His oldest daughter, Rose Blenkner, lives in Columbus, Montana. His son, Maj. Joseph B. Marsh, is an Air Force pilot stationed in Missouri. His younger daughter, Deanne Blaylock, is married to an ABC television technician assigned to the Presidential Press Corps and lives in Arlington, Virginia. He has nine grand-children.

TODAY show host Tom Brokaw also lived in Igloo as a child and attended school with the Marsh children. "Some people change in looks as they grow older," says Claudia, "But he didn't. The first time we saw him on television, we knew it was the same Tommy."

"One day Tom's little brother was missing, and we were really frightened because another little boy had drowned in one of the ponds," recalls Joe about an Igloo incident. The base had been thoroughly searched when Joe suddenly got and idea and went home. There, in his son's bedroom, he found the little Brokaw boy sound asleep. "He didn't even wake up when I carried him home," Joe happily recalls. "No one locked doors then and he played so often at our house that he'd just gone in to take a nap."

When he was 18, Joe converted to Mormonism and has been very active in the church, although its numbers are few in this area. For eight years, he served as president of the Hot Springs Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Claudia is also a Mormon convert.

Both he and Claudia officially retired in 1967 after working 25 years at Igloo. He continued his ranching pursuits and also worked five years as Custer County Weed Supervisor. In 1972 he was named to the Custer County Law Enforcement Commission and later was chairman of the Custer County-City Joint Law Enforcement Committee. He holds a lifetime South Dakota Peace Officer certificate.

In 1977 following Joe's open heart surgery, the Marshes sold their ranch and moved into Custer. He serves on a variety of committees and is still a special deputy for the Custer County Sheriff's Department. "I'm about the busiest retired person around," Joe will tell you with a grin.